The Greatest Team That Never Was

This is the story of the greatest American soccer team that never was.

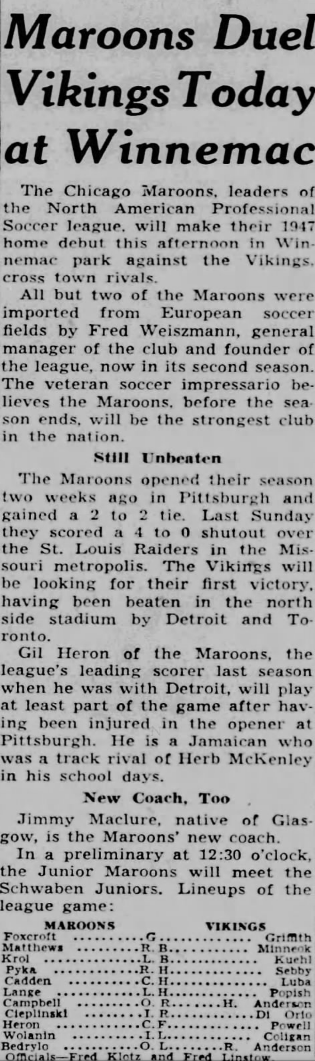

US soccer was in its heyday in 1980. The North American Soccer League, the country’s major league, was in its most stable and prosperous time. And, soccer, in general, had made it in America. Everything looked rosy for the sport that had so long been more promise than reality.

The American Soccer League was no different. The older, smaller sibling of the NASL did not operate at the same level, but the league seemed ready to break out of its semi-pro shell. A few years earlier the ASL finally became a truly national league when it expanded to the west coast. And, in 1980, the league expanded into Arizona, a soccer community that even the NASL had yet to tap.

In late June of 1979, Leonard Lesser, a Phoenix insurance executive and president of Phoenix Professional Sports Inc., which included five unnamed associates, purchased the NASL Memphis Rogues for a reported $1.6 million plus $1 million in debts. The Phoenix investors hinted that, if the sale was approved by the league, the franchise would likely be moved to Phoenix.

A week later, Rogues owner Harry Mangurian, rejected the offer of the Phoenix group to buy the NASL franchise. While Mangurian refused to reveal the issue, a newspaper article at the time revealed that Phoenix Professional Sports had not been able to come up with the necessary cash deposit of $200,000 nor a “proper” profit and loss statement. Lesser, claiming that the Phoenix group had a net worth of about $100 million, disagreed that the sale was off and expected to pay a $650,000 security bond. The sale was never finalized.

Two months later, in September, Lesser’s Phoenix Professional Sports, Inc. acquired an expansion franchise for Phoenix in the ASL. The official announcement was made at the Phoenix Press Club with “retiring” ASL commissioner Bob Cousy and Phoenix mayor Margaret Hance on hand. The announced cost of an ASL franchise at that point was $250,000 and Lesser said that the team’s operating expenses would be over $500,000 for the 1980 season. The team would play at Phoenix College’s Hoy Field where it would need to have an average attendance of six to seven thousand to break even. The average ASL attendance was about 3,800 per game.

It was also announced that Phoenix’s head coach would be Jim Gabriel. He had been the head coach of the Seattle Sounders for the past three years and resigned from the team only six weeks before. Lesser contacted him only a few days after the resignation and Gabriel inked a five-year contract with PPS. Lesser named himself general manager of the nascent team with Gabriel to be assistant GM. Gabriel brought Harry Redknapp, his assistant coach in Seattle, with him to Phoenix as an assistant coach and player.

In December, Jerry Underwood of Phoenix won a name-the-team contest and the team was dubbed the Phoenix Fire. The team officially signed a lease with the state to use Hoy Field for the season. And, Gabriel, with seemingly deep pockets, began signing players.

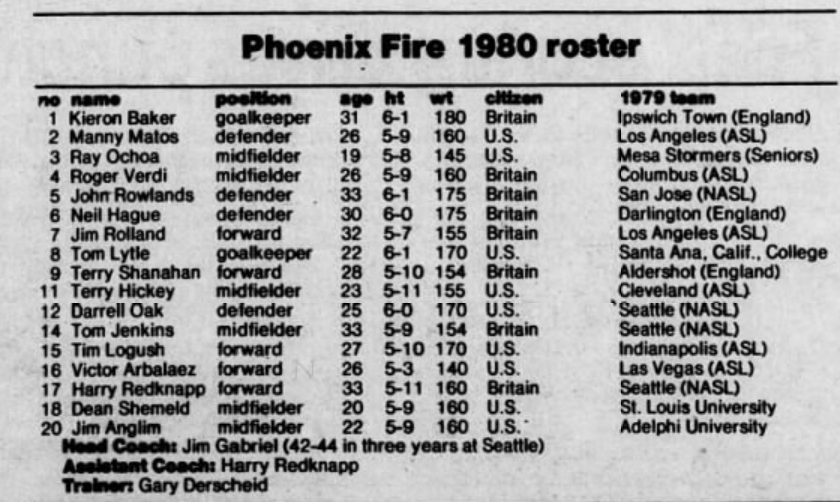

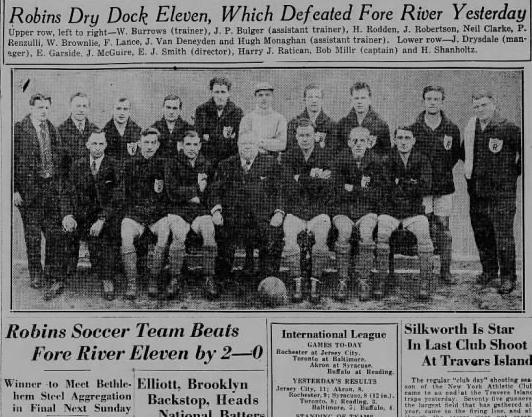

Roger Verdi was the first player signed to the expansion franchise. Born Rajinder Singh Virdee to Indian Sikh parents, his family moved to England when he was a child and he eventually changed his name due to racism. Playing with youth clubs in England, Verdi, a defender, moved to North America when he was not offered a professional contract by an English club. Verdi played in the NASL from 1972 to 1978 and then moved to the ASL in 1979 helping the Columbus Magic make the league finals.

Later that month, the team signed three more players. The first two were Terry Hickey, a midfielder from London, and Darrell Oak from North Dakota. The fourth player signed was New Yorker Manny Matos who had won the 1974 NCAA Division II championship with Adelphi University. All three of the signees had previously played for Gabriel in Seattle.

On January 11, 1980, the ASL held its annual college and territorial drafts in Charlotte, North Carolina. The Fire selected eight players in the draft including Henry Valdez, from Mesa High School, as its very first draft pick during the territorial round. Of those players, only the team’s final pick, Jim Anglim, a midfielder from Adelphi University, made the final roster.

At the end of January, the Fire signed two more players. Victor Arbelaez was a Columbian forward who had helped the University of San Francisco win an NCAA soccer championship in 1975. Aarbelaez was also a veteran of the ASL and NASL as well as the Major Indoor Soccer League. His claim to fame in the major league was scoring the only goal for the Las Vegas Quicksilvers in a 1-0 win against the legendary 1977 New York Cosmos team.

But, the bigger story for the Phoenix soccer community may have been the signing of Ray Ochoa of Mesa. Only 19 years old, Ochoa had been an all-state athlete at Mesa Westwood High School and played for the Mesa Stormers of the Arizona senior league.

On February 11, the Fire announced the signing of three veteran players which announced to the rest of the ASL that the expansion team would be a force to be reckoned with for the 1980 season. Scottish striker, Jimmy Rolland, had spent the prior four seasons with the ASL’s Los Angeles Skyhawks. Rolland had helped the Skyhawks to the 1976 ASL championship in their first season and was the team’s leading scorer and league MVP as the team made the ASL final in the 1978 season.

Another big signing was Liverpudlian, John Rowlands. The defender (and sometime forward) had been a journeyman in the English Football League before joining the NASL as a teammate with Jimmy Gabriel with the Seattle Sounders in 1974 and 1975. Rowlands was acquired from the NASL’s San Jose Earthquakes to play for Phoenix.

The other signing from England was Tom Jenkins. The midfielder had been a teammate of Jim Gabriel at Southampton during the late sixties and early seventies then joined Gabriel at the Seattle Sounders later in the decade. While Rollands and Rowlands were still starters when they joined Phoenix, Jenkins had barely played more than a handful of matches for Seattle the prior two seasons. Immediately before joining the Fire, Jenkins had played regularly for the Pittsburgh Spirits of the MISL during the league’s inaugural 1979-80 season.

Along with building a competitive roster, the expansion Fire also made outreach with the Phoenix community. Along with the signing of Ochoa, the Fire’s staff also took part in a celebrity soccer match against local celebrities. The outreach seemed to work as the Fire’s season ticket sales of 900 was second in the league only to the Pennsylvania Stoners’ 1100.

The team hoped to make a big splash in its first real match by hosting the NASL’s Chicago Sting on February 22 at Hoy Field. A week prior, Jim Gabriel had only had a chance to hold two practices for the expansion team but had begun having daily morning practices at Grand Canyon College leading up to their first match.

Four more players, bringing the total to 16, were signed the Tuesday before the match with Chicago. Forward Harry Redknapp was officially signed as a player and assistant coach. Redknapp brought goalie Kieron Baker out of semi-retirement to join the Fire. The pair had been teammates with Bournemouth. Baker had been the regular goalkeeper for most of that time, but was on the roster of Ipswich Town during the 1978-79 season. He never played for the first team and retired at the end of that season due to injuries.

Two more journeyman English leaguers were also signed. Defender Neil Hague, previously with Darlington, had also played with Redknapp at Bournemouth. And, forward Terry Shanahan had previously been with Aldershot.

Rounding out the roster were a trio of Americans. Tim Logush was the most experienced. The forward won the 1971 U.S. National Amateur Cup with Kutis S.C. of St. Louis and won two NCAA soccer championships in 1972 and 1973 with the Saint Louis Billikens. Logush was drafted by the NASL’s Seattle Sounders in 1975 but only saw action in four games. That same year Logush earned a cap with the U.S. Men’s National Team during a 4-0 loss to Poland on June 24. Logush went on to play in the ASL with the New Jersey Americans and Indianapolis Daredevils before joining the Phoenix Fire. Another young Saint Louis University player, Dean Shemeld, signed with the Fire after traveling from Milwaukee for an open tryout. Finally, backup goalie, Tom Lytle, had previously played with the Santa Clara College Dons.

That Friday, with an announced attendance of 9,809, the Phoenix Fire defeated the Chicago Sting in a 2-1 come-from-behind rally. Chicago’s German striker, Arno Steffenhagen, scored unassisted in the fifth minute after intercepting a pass. Neither team scored the rest of the first half as Phoenix put little offensive pressure on the Chicago goal.

Gabriel made tactical adjustments at halftime to play wider to the wings. He moved John Rowlands up from defense to take advantage of the player’s height and gave Terry Shanahan more freedom on the pitch. The changes gave more variety to the Fire’s attack.

With 25 minutes left to play, Steffenhagen was sent off for multiple fouls giving Phoenix the man advantage. In the 72nd minute, Shanahan crossed the ball from the left corner to Rowlands who headed the ball in from 18 yards out. Shanahan won the game in the 87th minute scoring a goal from 10 yards out on a centering pass from Tim Logush.

The Fire’s next match was a preseason game against fellow ASL expansion team, the Golden Gate Gales which were based in the Bay Area. Although the team was riding high after the game against the Chicago Sting, the Fire would be without the services of their starting goalie for two months as Baker had broken a knuckle during the match. But, backup goalie Lytle, handled the situation well and, on March 1, Phoenix defeated the Gales 1-0 at Hoy Field on a goal by Jimmy Rolland.

The Fire’s biggest challenge was yet to come. They were due to face the Mexico National Team on March 11 at Hoy Field. At this point, Mexico’s young superstar forward, Hugo Sánchez, was not only playing for his national team but also with UNAM of the Mexican Primera División and the NASL’s San Diego Sockers in the off-season.

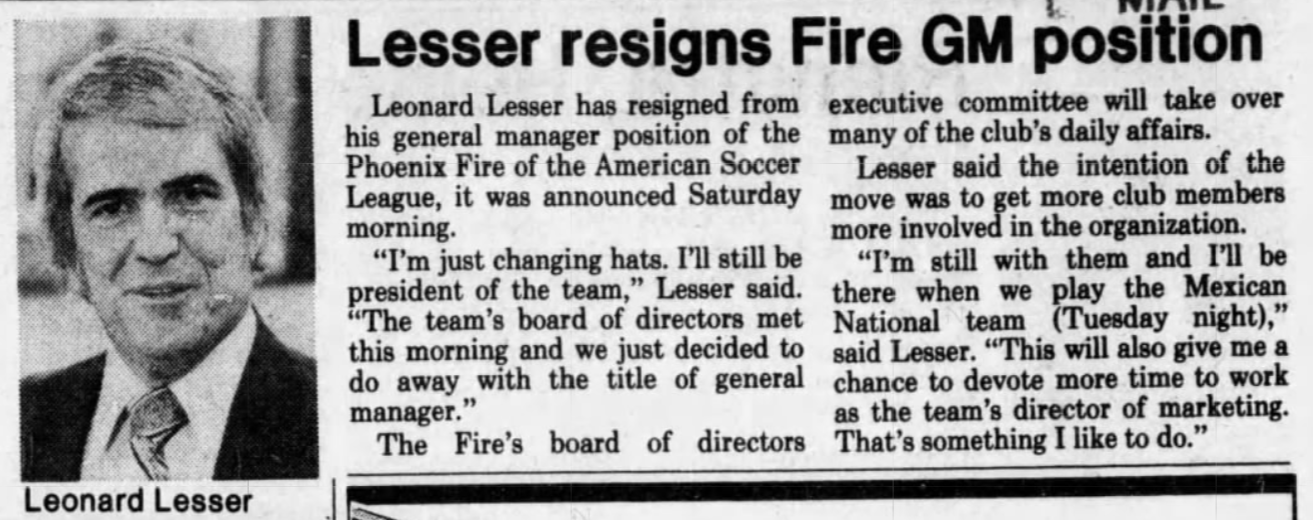

A few days before the match, storm clouds began developing over the Phoenix Fire organization. Lesser stepped down as general manager of the team and the board of directors decided to take a more active role in the team’s management.

The Mexican National Team dominated the Fire 3-0 in front of 3,500 at Hoy Field. Jim Gabriel tasked the young Mesan, Ray Ochoa, to mark Hugo Sanchez. While Ochoa held his own in the first half, Sanchez outclassed the rookie in the second.

Jorge Malo Lopez put the Mexicans on the board in the 20th minute scoring off a rebound on an indirect kick. Sanchez received a pass from Juan Luis Gonzales from the right corner and scored in the 55th minute. And, with less than six minutes to play, Ochoa fouled Sanchez leading to a penalty kick that the superstar converted.

The Phoenix Fire had one more preseason match on March 14 at Hoy Field against the Sacramento Gold, 1979 ASL champions, before their first regular season began on March 22 at home against the Golden Gate Gales. Jim Gabriel had finalized his roster, a mix of experienced English league veterans and young Americans, that he hoped would contend for the 1980 ASL championship.

But off the field, the Fire was in trouble. Papers began reporting that sources inside the organization said the team was in financial crisis and unable to meet certain obligations. The Gold were promised $2,000 plus expenses for two preseason games but the team was unsure if the payment would be made. In addition, the ASL had ruled John Rowlands ineligible because the check used in the transaction to acquire the player could not be cashed by the San Jose Earthquakes. Rowlands could not play against Sacramento.

According to players and front office personnel, Leonard Lesser did not so much as resign but was removed by his fellow investors. The club had a letter of credit for $1.5 million over three years with $500,000 earmarked for losses each season. But, after finding out that Lesser had severely over budgeted the organization, the remaining investors stepped in to jointly operate the team until a new general manager was found.

Sacramento beat the Fire 1-0 on an Anselmo Vicioso goal from 30 yards out. Only 500 were in attendance to see the exhibition. Coach Jim Gabriel subbed himself into the match at the striker position near the end of a match. The move was a personal superstition Gabriel had to play a few exhibition minutes each season.

The ASL governors flew to Phoenix the day after the Sacramento preseason match in hopes of finding a strategy to save the Fire. Their main plan was to severely cut back on player salaries and promotions.

Lesser had inked some players to $35,000 contracts. And, with the average player salary in the ASL at $12,000 to $15,000, officials were uncertain how Lesser expected to pay such high salaries with only 14 home games. In addition, the Fire had spent $50,000 to expand Hoy Field to 15,000 seats from 9,000 even though no ASL team had ever averaged 9,000 fans. Lesser had already committed over $500,000 before the season even began.

Players were found to have not been paid and checks issued by the club bounced. Even though they had not been paid, the players agreed to play the second, newly scheduled preseason match against Sacramento on Sunday, March 16.

The Fire and the Gold drew 1-1 on Civitan Soccer Sunday at Amphitheater High School in Tucson. Arbaelez scored on a header from a Rolland pass in the 9th minute. And Mike Mancini tied it up in the 30th minute after intercepting a Phoenix back pass. But the 3500 in attendance saw a substandard affair caused by the narrow high school football field and, likely, disinterested players.

On March 18, four days before the Phoenix Fire played its first regular season game, the team’s PR director, Joe Daggett, intended to put out a press release about the organization’s status. He was unable to complete the task because a leasing company had taken back the team’s typewriters.

Lesser was still optimistic that the Fire would play its first match, but coach Gabriel and the investor group working to save the franchise were extremely pessimistic. Sources indicated that most of the essential office equipment was gone, the team had missed its payroll for players and staff, and was $100,000 in debt. Financial obligations such as rent and installation of bleacher seats at Hoy Field and travel costs to bring in foreign players had gone unpaid.

Players were unsure of their next move and even how they would get back home. Jim Gabriel planned to borrow money to move his family back to Bellevue, Washington and then sell his house there to start over. He had been contacted by the San Jose Earthquakes for a coaching position but was unable to negotiate while under contract with Phoenix.

“This team could have won the ASL,” he said.

The next day, at a board of directors meeting for the club, Leonard Lesser resigned as president and member of the board, but retained his stock interest. Lesser then came up with $450 in cash, which Jim Gabriel split among the players at $20 a piece.

Even though the writing was on the wall, the Fire’s management refused to issue a statement concerning the official status of the club. With only a day before the opening game of the ASL season, the league and the Fire’s opponent, the Golden Gate Gales, had to assume the game was still officially on until formally told otherwise.

A group of fans quickly formed the “Friends of Soccer” group that set up a benefit game for the players to be played the same night as the all-but-cancelled league match at Hoy Field. The game would match the Fire players against an Arizona all-star team with profits going to help with players’ living expenses and travel costs back to their homes.

Phoenix College announced the field would not be available for either the Fire or the benefit game unless they were paid the $1708 rental still owed. And, while the Gales were still expected to arrive for their scheduled game, the ASL reported that the Fire had still only registered three of its players. If the Fire were to play the other players illegally, the game would be declared a forfeit and Phoenix would be fined $10,000. Neither the league nor the Gales nor even the Friends of Soccer could do anything until they had official word on the status of the club from the Phoenix Fire.

“We were taken in,” said an ASL owner. “It should never have happened.” - The Sacramento Bee, 21 March 1980

Phoenix Professional Sports released Phoenix College from its game day contract allowing the Friends of Soccer to hold its benefit game at Hoy Field. Phoenix College cut its normal rental fee by $1,000 dollars for the group. The league officially postponed the regular season opener, giving Fire officials until midweek to find new owners or investors.

The Fire players beat the team of Valley amateurs 5-0 in front of 660 paid spectators. After expenses, each player received $21.33. This was all the cash players had received since March 1.

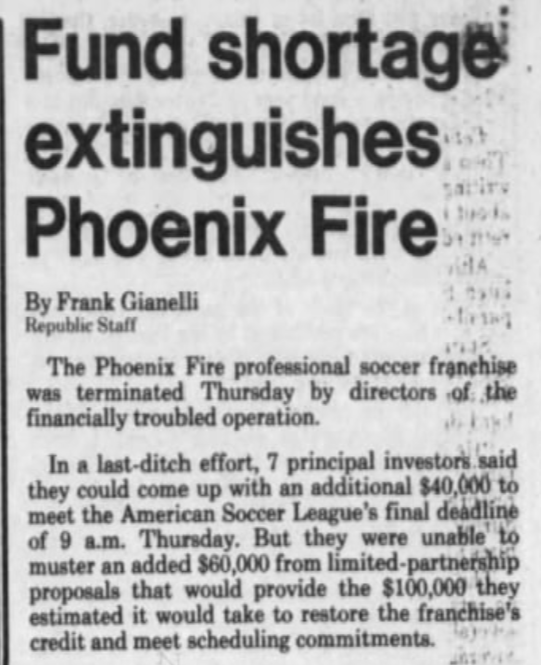

Mel Shimek, one of Phoenix’s co-owners, was still working to get investors. The group had been able to come up with $40,000 but were still hoping to raise another $60,000 via small investors coming in under limited partnerships. Jim Gabriel was willing to stay if things turned around, but had to drive back to Bellevue with his family leaving Harry Redknapp in charge of the club. Redknapp didn’t mince words, placing the blame squarely on Lesser. He stated that Lesser had missed paychecks as early as January 15.

On Thursday, March 28, the Phoenix Fire’s ASL franchise was terminated by the club’s board of directors.

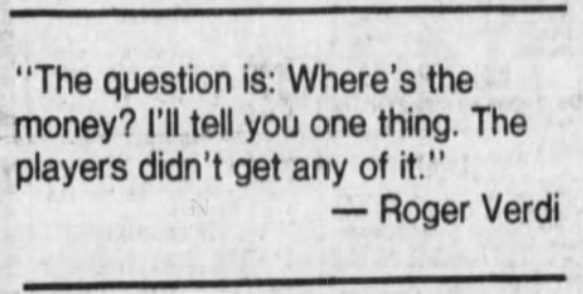

After the experience, Roger Verdi, estimated to have a salary of $35,000, was angry at both the club and the league. He dubbed the ASL “a nickel and dime operation” and vowed never to play for the league again unless they paid him up front.

A few months later, in July, Verdi was again the first player signed by a Phoenix expansion franchise. This time it was the Phoenix Inferno of the MISL. Verdi would play the entire 1980-81 season for the Inferno before retiring and moving into coaching.

Jimmy Gabriel borrowed $5,000 from friends to move his family back to Bellevue. Once there, he put his house up for sale in order to pay off debts accrued due to the debacle in Phoenix. In October, Gabriel would be hired by the San Jose Earthquakes to become their new head coach.

In November, Leonard Lesser was back in the news. In New York, he held a press conference to announce the formation of a 10-team U.S. Soccer League which would use only American-born players and begin in the spring. Later that week, Harvey Greenberg, a Phoenix investment counselor who would be the founder of the league’s Phoenix franchise, stated that he conceived of the venture and Lesser had only been invited because of his acquaintance with the NASL and ASL. Nothing came of the league as prospective members were hesitant to associate themselves with a venture connected to Lesser.

In January of 1981, Lesser was indicted by a Maricopa grand jury with conducting a fraudulent scheme, six counts of securities fraud, three counts of theft, and four counts of falsifying corporate records. County attorneys alleged that Lesser overstated the value of Phoenix Professional Sports in order to obtain investments and siphoned money from corporate accounts for his own unauthorized use. Lesser was also accused of falsifying corporate balance sheets and check registers to prevent investors from uncovering the true state of PPS’s finance and to cover his own thefts. Investors were alleged to have lost $200,000.

During the investigation, Phoenix police discovered that Lesser had also written a fraudulent check for the $200,000 down payment in the attempted purchase of the Memphis Rogues. The check bounced because the investigation found that the bank account never had a balance of over $50.

In August, Lesser was found guilty of defrauding investors but acquitted in 10 other criminal violations. That December he was sentenced to serve one year in Maricopa County jail and seven years probation plus 300 hours of community service after his release. He was allowed to remain free on a $10,000 bond pending his appeal. The verdict was upheld by the Arizona Court of Appeals in June of 1983.

- Dan Creel

IMAGES

OutOfShapeBowl: Feb 16, 1980, Arizona Republic

FireVsChicago: Feb 20, 1980, Arizona Republic

LesserResigns: Mar 9, 1980, Arizona Republic

Mexicans: Mar 11, 1980, Arizona Republic

FireRoster: Mar 14, 1980, Arizona Daily Star

FireExtinguished: Mar 28, 1980, Arizona Republic

VerdiQuote: Mar 29, 1980, Arizona Republic